What I Learned from Every Annual Letter of Terry Smith

Terry Smith's Fundsmith: Essential Takeaways from His Annual Letters

“My dad did not set out to make Walmart the world’s largest retailer. His goal was simply to make Walmart better every day, and he thought constantly about how to do just that.”

When Sam Walton built Walmart, his goal wasn’t to make it the world’s biggest retailer; he just wanted to make it better every day. This approach really resonates with me and my own investment journey. Inspired by Walton’s focus on daily improvement, I’m committed to keep on learning daily as well. Join me as I explore and learn, always aiming to be a bit better than yesterday.

I'll be covering the following key lessons I learned from reading all the annual letters of Fundsmith from the quality investor, Terry Smith.

The Investment Philosophy of Terry Smith

Why Investing in Bad Companies is a Problem and Why Buffett Changed from Value to Quality

The Importance of Return on Capital (ROIC)

Why Return on Capital (ROIC) Is More Important Than Earnings per Share (EPS)

The Importance of Retaining Earnings (Instead of Paying Dividends)

Intangibles: Understanding the Value of Modern Assets

Why Does Quality Come with a Hefty Price?

Most of the Market Returns Come from a Few High-Quality Stocks

Why Timing the Market is a Bad Idea

Don’t Own Too Many Stocks

Lessons Learned from his Best Investment (Domino’s Pizza)

#1 The Investment Philosophy of Terry Smith

Terry Smith's investment approach is all about simplicity and long-term value. At the core of his strategy is a focus on high-quality companies that generate consistent returns. In his 2011 letter, Terry Smith summed it up perfectly: “Buy great businesses which we have purchased at reasonable prices or better and which we intend to hold onto in order for them to deliver the benefits of such investments.” That sounds great, but what does he really mean by “great businesses” and a “reasonable price”?

As a fund manager, Terry needs his clients' money to invest, so he builds trust by sticking to three (oversimplified) main rules:

Invest in Good Companies

Don’t Overpay

Do Nothing

However there's a bit more to it than just that. Let's dig into his philosophy a bit more.

Invest in Good Companies

When Terry Smith talks about “good companies” versus “bad companies,” he keeps coming back to one main idea: Good companies create value for shareholders by making a high return on capital, way above their cost of capital, throughout different business cycles. Bad companies, on the other hand, destroy value because their return on capital is lower than their cost of capital.

I’ll get into the details of this later in section #3 on the Importance of Return On Capital, but it’s an important one to remember, so I’ll repeat it: Good companies create value by consistently earning returns on capital that exceed their cost of capital. In contrast, bad companies destroy value by earning returns on capital that are lower than their cost of capital. I’ll get into the nitty-gritty of this concept later on. All in all, when Smith mentions “good companies” or “quality companies”, this is the key point to remember.

Aside from his main rule, Smith also gives us more specifics on what he calls quality companies. As a matter of fact, Smith only invests in companies that have:

High Returns on Capital (ROIC): These companies make a lot more money from their investments than they spend.

Source of (Organic) Growth: High returns don’t mean much if the business can’t grow. These companies grow naturally without having to buy other companies and can keep growing for a long time. Plus, they reinvest their earnings at those high returns.

Converts Most/All Profits into Cash: Smith likes companies that turn 90-100% of their net income into cash because it means more money for things like further investments or paying back shareholders.

High Profit Margins: These companies have solid profit margins, both gross (after production costs) and operating (after all business expenses).

Resilient to Economic Cycles: They’ve proven to be tough and can handle economic ups and downs over many years.

Strong Balance Sheet: They have low debt and plenty of coverage for their interest payments.

I might have missed a few other things Smith thinks highly of in his search for quality, but these ones became clear to me after reading all of his letters.

Smith’s philosophy can be summed up in three words: “Quality Over Value.” He’s more interested in the quality of a business than just finding undervalued stocks. (More on that later too.)

What doesn’t Smith want to own?

Knowing what you want to own is important, but as Charlie Munger would say: “Invert, always invert.” Let’s take a look at what Terry Smith doesn’t want to own to get a clearer picture of his investment strategy.

Avoiding Banks and Financial Stocks: In 2013, Smith talked about avoiding banks and financial stocks entirely. He believes these are cyclical companies, and it's difficult for fund managers to consistently make profitable trades in this sector.

Avoiding Cyclicals and Highly Leveraged Companies: In 2014, Smith repeated his avoidance of cyclical industries like consumer discretionary, industrials, finance, information technology, and energy sectors. Besides that Smith avoids highly leveraged companies that might benefit from a recovery but are at risk of going bust otherwise.

Shunning Short-Term Trends and Healthcare Booms: In 2016, Smith didn’t participate in the healthcare boom and generally avoids shorter-term investments. He dislikes companies that won’t last indefinitely because investors relying on these trends will need to constantly find the next hot sector. His strategy focuses on long-term investments in companies with enduring value.

By understanding what Smith avoids—cyclical sectors, highly leveraged companies, and short-term trends—we can better appreciate his focus on high-quality, resilient businesses that generate strong returns even in challenging economic conditions.

Don’t Overpay

Even for the best companies out there, you don’t want to overpay. Paying too much for even the highest quality company can still make it a bad investment. But as Smith points out, there’s nothing wrong with paying “reasonable prices” for quality businesses.

Let’s dive into one of Smith’s famous thought experiments on “Justified P/E’s,” or figuring out which price-to-earnings ratio you could have paid for a top company to still beat the market. In his 2022 letter, Smith included a graph showing that you could have paid insanely high P/E ratios for certain stocks in 1973 and still outperformed the market over the next 30 years, thanks to the magic of compounding.

For example, you could have paid 281 times earnings for L’Oréal, 174x for Brown-Forman, 100x for PepsiCo, 44x for Procter & Gamble, or 31x for Unilever. But don’t get too excited! Smith isn’t saying you should pay these multiples today. Instead, he’s pointing out that high P/Es don’t always mean a stock is too expensive. It could still pay off big time if you look deeper instead of instantly rejecting any stock trading above 20 times earnings.

I’m not entirely sure about Smith’s whole valuation process, but the silver lining from his letters is that Terry Smith really zeroes in on the Free Cash Flow Yield of his companies instead of just looking at P/E ratios (or the Earnings Yield).

Free Cash Flow Yield (FCF Yield)

Smith aims to buy stocks when their FCF yield is at least as high as what you’d expect from long-term government bonds in the same currency. He doesn’t base this on today’s low yields but on a scenario where all bonds were sold to third-party investors, usually about 1% above the expected inflation rate. This way, the FCF yields of the stocks he buys are higher and will keep growing, unlike fixed bond coupons.

Why Focus on Free Cash Flow Yields?

Smith prefers FCF yields over P/E ratios because not all earnings are the same. The companies he picks are less capital-intensive and have higher returns on capital than the market average. They turn 90-100% of their earnings into cash, which is crucial since cash pays the bills, and cash earnings are more reliable than non-cash ones.

Quality and Price

Since Smith invests in quality companies, their shares often have higher price tags. Critics might say these shares are "too expensive.” However, he doesn’t give much attention to the “too expensive” critics, noting that following their advice could have been costly. He doesn’t try to time the market and focuses on long-term value instead.

Smith’s strategy shows that while quality companies often have higher prices, what matters is making sure the price is justified by the company’s ability to generate and grow free cash flow. By focusing on FCF yields and the long-term growth potential of high-quality companies, Smith aims to avoid overpaying and capture lasting value.

Do Nothing

As Warren Buffett put it, “The stock market is a device for transferring money from the impatient to the patient.” Basically, long-term investors who stay cool and hold onto their investments usually do better than those who keep trading or panic sell. That’s why “doing nothing” is the third and final step in Terry Smith’s investment approach.

To explain this, Smith uses a Tour de France analogy. In his 2013 letter, he said: "We don’t aim to outperform in every reporting period or under all market conditions. Instead, we aim to outperform the market and other funds over longer periods."

The Tour de France, which has been running for over 100 years, has three very different types of stages:

Peloton Stages

Time Trials

Mountain Stages

A rider needs a very different physique to win as a sprinter, a time trialist, or a mountain climber. That’s why no rider has ever won every stage of the Tour. In fact, there have been two times when the Tour was won by a rider who didn't win a single stage (out of the 21 stages)!

So, what’s the lesson for investors?

For investors, the takeaway is clear: aim to outperform over the long haul (like winning the whole Tour), not in every single moment or market condition (like winning every stage). Expect to do well in bear markets and maybe not keep up in bullish ones. Too often, investors chase constant outperformance, switch strategies, incur costs, and abandon approaches that fall out of favor. That’s not a winning strategy. Practice doing nothing most of the time.

#2 Why Investing in Bad Companies is a Problem and Why Buffett Changed from Value to Quality

The Problem with Investing in Low-Quality Businesses

The biggest issue with investing in “low-quality businesses” is that their poor return characteristics tend to persist over time. Good sectors and businesses continue to perform well because they have competitive advantages—what Warren Buffett calls ‘The Moat.’ These moats can include network effects, switching costs, economies of scale or intellectual property (like a strong brand or patents).

Conversely, businesses with many competitors, no control over pricing or input costs, and products that consumers can defer buying during downturns (like cars) generally continue to struggle. Just because these companies are cheap or benefit from an economic recovery doesn't mean they'll become good long-term investments.

Even if you manage to buy a cheap value stock and time it right, it won't necessarily transform into a good business. You'll need to sell it at the right moment, which is tough because its inherent poor quality won't improve over time. Buffett summed this up well in his 1989 letter to Berkshire Hathaway shareholders:

“The original ‘bargain’ price probably will not turn out to be such a steal after all. In a difficult business, no sooner is one problem solved than another surfaces - never is there just one cockroach in the kitchen. Any initial advantage you secure will be quickly eroded by the low return that the business earns. For example, if you buy a business for $8 million that can be sold or liquidated for $10 million and promptly take either course, you can realize a high return. But the investment will disappoint if the business is sold for $10 million in ten years and in the interim has annually earned and distributed only a few percent on cost. Time is the friend of the wonderful business, the enemy of the mediocre.”

This encapsulates the primary issue with investing in low-quality businesses: they tend to have persistently poor returns. Even if you buy them at a bargain price, these companies often struggle with recurring problems and fail to generate sustainable, high returns over the long term.

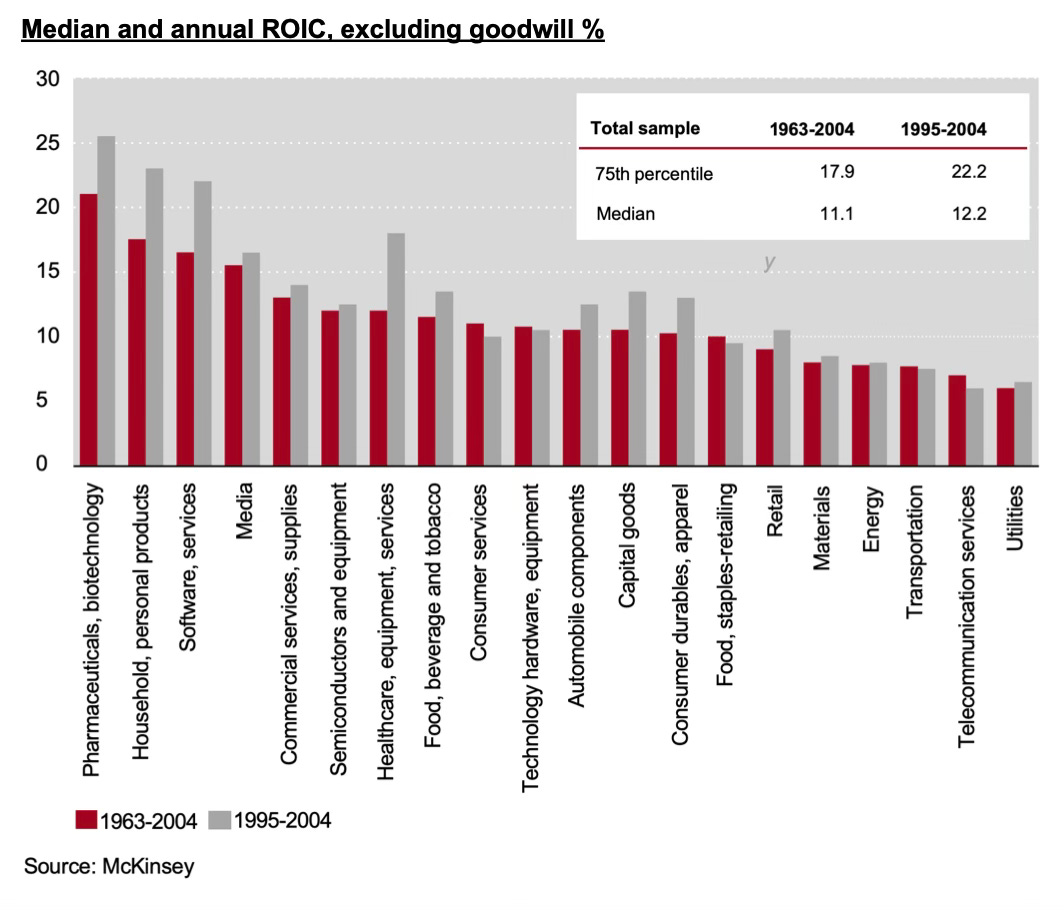

As you can see in the graph, good sectors and businesses tend to stay good, while those with poor returns continue to perform poorly. The charts below make this clear.

Terry Smith adds to this view, highlighting the disadvantages of the value investing strategy:

Long Wait for Value Realization: While waiting for an undervalued stock to appreciate, the company is likely not compounding in value. In fact, it may be destroying value.

Active Strategy with High Transaction Costs: Value investing requires continuously finding new undervalued stocks, which incurs higher transaction costs compared to a buy-and-hold strategy.

Missed Gains: Following value investment advice often leads to missing out on significant gains from high-quality companies that consistently compound over time.

Persistent Problems with Low-Quality Investments

Persistent Poor Returns: Low-quality businesses, characterized by numerous competitors, lack of pricing power, high input costs, and products that can be easily deferred by consumers, tend to have persistently poor returns.

Difficulty in Transforming Business Quality: Even if you manage to buy a truly undervalued stock and time the market correctly, this doesn’t transform it into a good long-term investment. The company’s inherent poor quality remains a drag on performance.

Need for Timely Exits: Success in value investing often requires selling at the right moment, which is challenging to predict and execute consistently.

Buffett’s Shift to Quality

Buffett's shift to investing in high-quality businesses was driven by the realization that mediocre businesses, despite being bought at a bargain, often fail to deliver satisfactory long-term returns. In contrast, high-quality businesses can sustain growth and compounding over time, making them far superior investments. By focusing on businesses with durable competitive advantages, Buffett found that these investments could deliver much better long-term returns with less effort and risk.

In summary, both Buffett and Smith highlight the importance of investing in high-quality companies over bargain hunting for low-quality stocks. The persistence of poor returns in low-quality businesses and the challenges of timing the market correctly make high-quality, durable businesses the better choice for long-term investors.

#3 The Importance of Return on Capital

When Terry Smith talks about returns on capital, he constantly mentions Return on Capital Employed (ROCE), but most investors look at Return on Invested Capital (ROIC). Is there a big difference? While the calculations differ, investors and analysts often use ROCE and ROIC interchangeably when discussing capital efficiency and returns. While technically there are differences in their calculations, the underlying principle is pretty consistent. For simplicity, I'll stick with ROIC here.

Good Companies Create Value

Remember Smith's main rule: Good companies have high returns on capital (ROIC). When you invest in bonds, stocks, or even a savings account, your main concern is the return you'll get. Buying shares of a company means you're purchasing a portion of its capital. Naturally, you want to know what return that capital is generating right? I mean, it’s partly yours.

Consider this simple example: if you borrow money at 5% interest and invest it at a 10% return, you're making a profit and creating value. Conversely, if your investment only returns 2.5%, you're losing money and destroying value. The same principle applies to companies. Those with returns above their cost of capital generate value for shareholders, while those with lower returns reduce it.

Cost of Capital

The term "cost of capital" or “WACC” (Weighted Average Cost of Capital) can seem tricky, but it's an essential concept to grasp. So, what is it exactly? The cost of capital represents the company's expense for financing its operations through both debt and equity. It's straightforward to determine the cost of a company's debt from their annual reports, but calculating the cost of equity capital is more complex and usually not worth the effort to calculate precisely.

For quality companies, the cost of capital typically falls within the range of 8-11%. Here's the key takeaway: focus on companies whose returns on invested capital (ROIC) are high enough to exceed any reasonable cost of capital. Most savvy investors aim for companies with ROICs above 15%. This way, you can be sure that the company is creating value for you as a shareholder rather than destroying it.

Not convinced about the importance of returns on capital? Even Warren Buffett emphasized this in his 1979 letter: "The primary test of managerial economic performance is the achievement of a high earnings rate on equity capital employed (without undue leverage, accounting gimmickry, etc.) and not the achievement of consistent gains in earnings per share."

By focusing on companies with high returns on capital, you can be more confident that your investments are creating value for you instead of destroying it. Oh, and what Buffett just said about ROIC > EPS, I’ll discuss that at #4.

Why Doesn’t Everyone Invest in High-ROIC Businesses?

You might be wondering, if it's so simple, why doesn’t everyone do it? Terry Smith asked himself the same question: “Why isn’t everyone solely investing in high-ROIC businesses?”

According to Terry Smith, some investors believe they can time their entry into shares of underperforming companies, hoping for a turnaround. They might expect a boost from a cyclical upturn, a change in management, or a potential acquisition. However, this strategy often overlooks the fact that these companies are gradually destroying value due to their poor ROIC.

On the other hand, investing in companies with high ROIC makes time your ally. With high-ROIC companies, you don’t need any specific event to happen for your investment to grow. The companies naturally create value over time, allowing you to ride the wave and benefit from their consistent performance.

Example: The Airline Industry

Terry Smith wrote about airlines as a prime example of a value-destructive industry:

“Some industries are prone to make returns below their cost of capital much or all of the time, like airlines. They have not created shareholder value throughout most of its existence. Why would anyone with their right mind invest in something which destroys value?

They hope that a change will come soon - new management, upturn in the business cycle, a takeover or industry consolidation - which lifts the share price up. Whilst they wait for their investments in bad companies to come good, they steadily erode value by the equivalent of borrowing money from the shareholder and investing it at an inadequate rate of return.”

Why Is Investing in Bad Companies a Bad Idea?

Despite the temptation of potentially undervalued shares, investing in ‘bad’ companies (ROCE < WACC) can be a long-term mistake. Here’s why:

Rare Transformational Improvement: Companies rarely undergo dramatic improvements.

Unpredictable Changes: It's hard to predict when these changes will happen.

Erosion of Value: While waiting for these companies to improve, they steadily lose value. Terry Smith compares this to waiting for a kiss to turn a corporate frog into a prince, but meanwhile, the company is eroding value.

Sure, even good companies are affected by economic cycles, and their share prices might drop by 50%. However, with high-quality companies, you can be reasonably sure they are adding to their intrinsic value over time. Investing in such companies allows you to weather the downturns, confident that the underlying business remains strong.

I found Terry Smith’s insights really eye-opening. It’s surprising that not all fund managers aim to invest in good companies. They might buy shares in bad companies (ROIC < WACC) hoping for temporary improvements. While this might benefit the share price, it’s generally a long-term mistake.

#4 Why Return on Capital Is More Important Than Earnings per Share

Many investors focus on growing earnings per share (EPS), but Terry Smith argues that return on capital employed (ROCE) is more crucial, or instead of ROCE, which I already discussed, the ROIC. Terry Smith isn’t the only one saying this. The Oracle of Omaha already preached this too in his 1979 letter as you could see earlier in my blog. I’ll repeat the quote here again:

Many investors focus on growing earnings per share (EPS), but Terry Smith argues that return on capital employed (ROCE) is more crucial, or as I’ve discussed ROIC. This view isn't unique to Smith; Warren Buffett, the Oracle of Omaha, emphasized it in his 1979 letter:

“The primary test of managerial economic performance is the achievement of a high earnings rate on equity capital employed (without undue leverage, accounting gimmickry, etc.) and not the achievement of consistent gains in earnings per share.”

ROIC vs. EPS

Terry Smith explains that while consistent EPS growth might look good, it can be achieved through methods like acquisitions, cost-cutting, and share buybacks, which aren't always high-quality growth strategies. Acquisitions can often destroy value unless done strategically. Cost-cutting and share buybacks are limited; you can't cut costs forever or "shrink your business to growth, other than growth in EPS."

Focus on High Returns on Capital

Smith highlights the importance of focusing on returns that exceed the cost of capital (WACC). EPS and PE ratios don't consider metrics like ROCE or ROIC. For example, even as Tesco's EPS rose, its declining ROCE showed potential value destruction for shareholders. Smith prefers ROCE as it measures value creation by delivering returns above the cost of capital, unlike EPS, which can be misleading.

All in all, the key takeaway is that a company can destroy shareholder value even if it consistently increases its EPS. High ROCE/ROIC is a better indicator of a company's true performance and ability to create value for shareholders.

#5 The Importance of Retaining Earnings (Instead of Paying Dividends)

Jack Bogle has a famous quote about the power of dividends:

“An investment of $10,000 in the S&P 500 Index at its 1926 inception with all dividends reinvested would by the end of September 2007 have grown to approximately $33.1 million (10.4% compounded). If dividends had not been reinvested, the value of that investment would have been just over $2.1 million (6.1% compounded) - an amazing gap of $32 million.

Over the past 81 years, then, reinvested dividend income accounted for approximately 95% of the compound long-term return earned by the companies in the S&P 500.”

Dividends vs. Keeping Earnings

So, does this mean dividends are more important than share price growth? Not exactly. Terry Smith adds some nuance to Bogle’s point. He argues that it’s not just about reinvesting dividends but also about the return on those reinvestments. If you spend the dividends, you won’t hit that $33.1 million mark; you'd end up with just $2.1 million. The key is reinvesting dividends in equities.

In Bogle’s example, you’d get an even higher return if you reinvested the dividends not in the entire S&P 500 but in companies that outperformed the index. You’d also fare better if companies kept all their earnings and reinvested them at a high rate of return. Take Berkshire Hathaway, for example. They’ve never paid a dividend because Buffett knows he can reinvest earnings at a higher return than the S&P 500. If Berkshire paid a dividend and you reinvested it back into Berkshire, you’d still lose out because of taxes.

So, it’s not just the dividend or even the reinvestment of the dividend that’s crucial. It’s the rate of return on the reinvestment that drives the overall return.

Compounding Power of Stocks

Stocks can grow in value in ways that bonds and real estate just can’t match. How? Companies keep and reinvest a portion of their profits back into the business.

In the S&P 500 (as of 2017), almost half of the earnings were paid out as dividends. The other half was reinvested in the business. Compare this to bonds, where you just get an interest payment that isn’t automatically reinvested, or real estate, where rental income doesn’t get reinvested into the property for you.

The ability to reinvest earnings is a big reason why stocks can compound over time. That’s why a high ROIC is so crucial. You want the internal compounding to happen at the highest rate possible! For instance, if a company earns a ROIC of 15% and reinvests 50% of its earnings, then half of its earnings get compounded by 15%.

Multiples and Market Value

Another attractive feature is that many companies trade at multiple times their book value (the S&P 500 was at 3x book value in 2017). This means that for every $1 of earnings retained, the company creates $3 of market value (assuming the 3x book value remains constant). This is different from reinvesting dividends.

The Tax Disadvantage of Dividends

When you reinvest dividends, you buy shares at market value, which was 3x book value for the S&P 500 in 2017. However, each $1 of retained earnings gets reinvested at book value, not 3x book value. Plus, dividends are taxed. Here’s the math:

Tax Impact: Dividend income is taxed at 32.5%, so you’re left with 67.5 cents out of every dollar to reinvest.

Market Price: You then buy shares at 3.5x book value (as it was in 2018), so you only get 28.5 cents of company capital for every $1 reinvested.

Net Effect: In total, every $1 of dividend paid out gives you 67.5 cents after tax, and just 19 cents of company capital (67.5 divided by 3.5).

In contrast, every $1 of retained earnings is reinvested at book value with no additional tax, giving you the full $1 in company capital.

It’s the reinvestment of retained earnings, not dividends, that provides the majority of growth in the value of stocks! When companies reinvest their earnings internally, they avoid the tax hit and market premium associated with dividends, leading to better long-term growth.

Retained Earnings vs. Dividends

If a company can reinvest its retained earnings at a higher-than-average rate of return, you never want them to pay out a dividend. This is exactly why Warren Buffett has never paid out a dividend at Berkshire Hathaway.

It sounds simple, but it’s tough for companies. This is because of “mean reversion,” where high returns attract competition, eventually reducing returns to the average. The small group of companies that manage to avoid this have a "moat," or a competitive advantage, that fends off competition.

It’s crucial for a company to have a source of growth that allows it to reinvest retained earnings at a high rate. Many companies start with good returns but then invest retained earnings at lower rates, destroying value for shareholders. So, when looking at investments, focus on companies that reinvest their earnings wisely and at high returns.

Conclusion

Terry Smith’s insights highlight that it's not just about paying or reinvesting dividends but the return on those reinvestments. Companies that can reinvest earnings at high rates of return will always outperform those that pay out dividends and can’t reinvest as effectively. So, when looking at investments, focus on the companies that reinvest their earnings wisely and at high returns.

Besides, I think it’s good to keep this passage of John D. Rockefeller, the richest man on earth then, on how he felt about dividends:

“Nothing nettled him more than directors who preferred fatter dividends to earnings plowed back into the business.”

#6 Intangibles: Understanding the Value of Modern Assets

When we talk about high-quality companies, we often think about physical assets like real estate, machinery, and equipment. However, many modern companies, especially in technology, rely heavily on intangible assets. These include brands, patents, copyrights, know-how, installed bases of equipment that lock in customers, crucial software systems, and network effects.

Why Intangible Assets Matter

Intangible assets often offer higher returns because they are funded with equity rather than debt, which attracts a higher return. Unlike physical assets, intangible assets can last indefinitely if maintained through advertising, marketing, innovation, and product development. This longevity is crucial in determining the real returns on these assets.

Challenges in Comparing Tangible and Intangible Assets

Comparing companies that rely on tangible assets with those that rely on intangibles can be tricky. Here’s why:

Balance Sheet Visibility: Tangible assets appear on the balance sheet when purchased or leased. In contrast, intangible assets are usually built through ongoing expenses like marketing, R&D, and brand development, which go through the profit and loss account and impact cash flow directly.

Profitability Distortion: This means that for the same level of investment, companies building intangible assets might look less profitable than those investing in physical assets. This skews comparisons based on simple metrics like price-to-earnings (PE) ratios.

The Rise of Intangible Investments

The importance of intangibles has been growing for decades. Since the mid-1970s, investments in intangible assets by US corporations have been steadily rising, surpassing investments in tangible assets in the 1990s as the internet age took off.

Impact on Market Valuations

This shift makes comparing different types of companies and assessing market valuations over time more complicated. For example, in 1964, the average company stayed in the S&P 500 for 33 years. By 2016, this had dropped to 24 years, reflecting the faster pace of change and the rise of intangible assets.

Why Companies with a Lot of Intangibles Need a Different Valuation Approach

Intangible assets change how we should assess a company's value. Here's three of the reasons Smith mentions in his letters:

Visibility and Accounting: Tangible assets (like buildings and machinery) show up on the balance sheet. Intangible assets (like brands and patents) usually appear as expenses on the profit and loss statement. This can make companies with many intangible assets look less profitable, but these expenses are actually investments in future growth.

Longevity and Maintenance: Intangible assets can last a long time if properly maintained. For instance, a strong brand or patent can keep generating returns. Unlike physical assets that wear out, intangible assets need ongoing investment to stay valuable.

High Returns: Intangible assets can deliver much higher returns than tangible assets. This is because they often create unique advantages, like customer loyalty or exclusive technology, which are hard for competitors to copy. So, valuation methods need to account for these higher potential returns.

By understanding these differences, investors can better judge the real value of companies with lots of intangible assets. Recognizing the unique qualities of intangible assets is crucial for making smart investment decisions in today's market.

Conclusion

Smith explained very clearly that understanding the value of intangible assets is crucial in today’s investment landscape. They offer significant long-term returns but require a different approach to valuation compared to traditional, tangible assets. As intangible investments continue to rise, investors need to adjust their strategies to accurately assess and compare the true value of companies.

#7 Why Does Quality Come with a Hefty Price?

The Challenge of Alternatives

If you believe that high-quality stocks are expensive and will give your portfolio a hard time in the short-term, you’re stuck with finding a good alternative. Why is that tricky?

Valuations in Context: The valuations of high-quality stocks in Smith’s fund aren’t drastically higher than the market average, especially considering their superior quality. While some say we’re in a “bubble,” predicting market trends is notoriously difficult. Even if a downturn happens, cyclical stocks and financials are unlikely to outperform high-quality, defensive companies that provide everyday necessities. The 2007-09 financial crisis supports this view.

Poor Long-Term Value in Cyclicals: Investing in cyclical, financial, and so-called ‘value’ stocks means putting money into companies that historically do not generate returns on capital above their cost of capital. They fail to grow by deploying more capital at favorable returns.

Munger’s Insight on Long-Term Returns

Charlie Munger provides a crucial insight: “Over the long term, it’s hard for a stock to earn a much better return than the business which underlies it earns. If the business earns 6% on capital over 40 years and you hold it for that 40 years, you’re not going to make much different than a 6% return—even if you originally buy it at a huge discount. Conversely, if a business earns 18% on capital over 20 or 30 years, even if you pay an expensive-looking price, you’ll end up with a fine result.”

Smith notes that this Mungerism is a mathematical fact. Investing long-term in companies that deliver high returns on capital and reinvest those returns effectively has a far greater impact on share performance than the initial purchase price.

Munger’s approach needs a long-term perspective to benefit from the compounding returns of high-quality companies. However, this is tough because of two reasons:

Finding high-quality companies that can sustain high returns and fend off competition is difficult.

Investors often find it difficult to stick to a long-term view (i.e. a lack of patience), especially when high-quality companies underperform compared to cyclical companies enjoying short-term gains.

Conclusion

Investing in high-quality companies may seem expensive, but it’s often worth it in the long run. High returns on capital and effective reinvestment lead to awesome compounding, which outweighs the initial high price. However, these companies are difficult to find and you need a lot of patience to let the magic of compounding do its work.

#8 Most of the Market Returns Come from a Few High-Quality Stocks

Terry Smith often references a research paper by Hendrik Bessembinder titled “Do Stocks Outperform Treasury Bills?”. The key takeaway: just over 4% of companies account for all of the wealth created in the stock market.

The Reality of Stock Returns

While stocks as a whole outperform bonds, most individual stocks do not. Positive returns are concentrated in a very small number of stocks. This means that most active investors end up underperforming not only the equity indices but also bonds. This underperformance is often due to fees, other costs, lack of skill, and institutional biases. But it’s also because many investors don’t focus on the few stocks that actually drive returns (the quality companies Smith talks about!).

The Opportunity for Smart Investors

This might sound worrisome, but it also creates opportunities for those who take investing seriously (like those reading this blog!). The key insight is that you can achieve large returns by selecting a concentrated portfolio of the few stocks that offer positive returns.

So, instead of spreading your investments too thin, focusing on high-quality stocks - while keeping the tips and tricks of Terry Smith in mind - can make a big difference in your overall performance.

#9 Why Timing the Market is a Bad Idea

I’ve already covered why timing the market is a bad idea. It was even Francois Rochon’s top idea, as he said: “It is futile to try and predict the stock market.” Terry Smith shares this view on market predictions.

The Difficulty of Market Timing

Buying low and selling high sounds simple, but it’s incredibly tough to pull off. Most investors end up doing the opposite—buying high and selling low. For example, if you missed the best ten days in the market from December 31, 1994, to 2004, your annual return would drop from 12.07% to 6.89%. Missing the best 30 days would result in negative returns. While avoiding the worst days would help, there are generally more good days than bad. Terry Smith asks, “Do you really think you are good enough to spot those days and make sure you are fully invested and ready for them? I know I’m not.”

Staying Fully Invested

Smith doesn’t make market timing judgments. Instead, he stays fully invested in high-quality companies, believing they will create value over time. Critics might say his stocks are too expensive, but Smith thinks staying invested is crucial to reap long-term benefits. According to Terry Smith, there are only two types of investors:

Those who know they can’t make money from market timing.

Those who don’t know they can’t.

Don’t Try to Predict the Market

Smith states that macroeconomic views and developments don’t influence his investment strategy. He believes that trying to predict and time the market is pointless. No one has ever reliably linked GDP growth to stock market performance. He emphasizes that regardless of the economic outlook, his view doesn’t change: “Fundsmith remains fully invested in high-quality companies that meet their rigorous financial criteria.” (2013, 2014)

Smith's Guiding Principles for Predictions

In his 2019 letter Smith has outlined guiding principles for dealing with market predictions:

No one can predict market downturns reliably.

Forecasters ignore that following their advice often leads to missing gains that far outweigh losses during downturns.

Bull markets do not die of old age.

Bull markets climb a wall of worry.

Bull markets narrow as they age, focusing on fewer stocks.

Buying ‘value’ stocks is best done after a bear market strikes, not before.

A bear market will happen eventually. The best stance is to ignore it since you can’t predict it or avoid it without missing gains.

Smith also highlights the difficulties in predicting market movements and currency fluctuations. Successful companies rarely attribute their success to currency exposure but to factors like product innovation and strong customer relationships.

The Dangers of Forecasting

Smith uses the 2020 pandemic as an example of the dangers of forecasting. Despite the economic impacts, it would have been hard to predict that the MSCI World Index would deliver a return of 12.3%, slightly above its ten-year average. He concludes with a humorous analogy: “What are the similarities between a forecaster and a one-eyed javelin thrower? Neither is likely to be very accurate but they are typically good at keeping the attention of the audience.”

#10 Don’t Own Too Many Stocks

Owning just one, two, or three stocks is way too risky for most investors (unless you’re Charlie Munger). But owning too many stocks isn’t great either because you’ll just end up tracking the index, and you might as well buy the index to save on costs. The sweet spot lies somewhere in between.

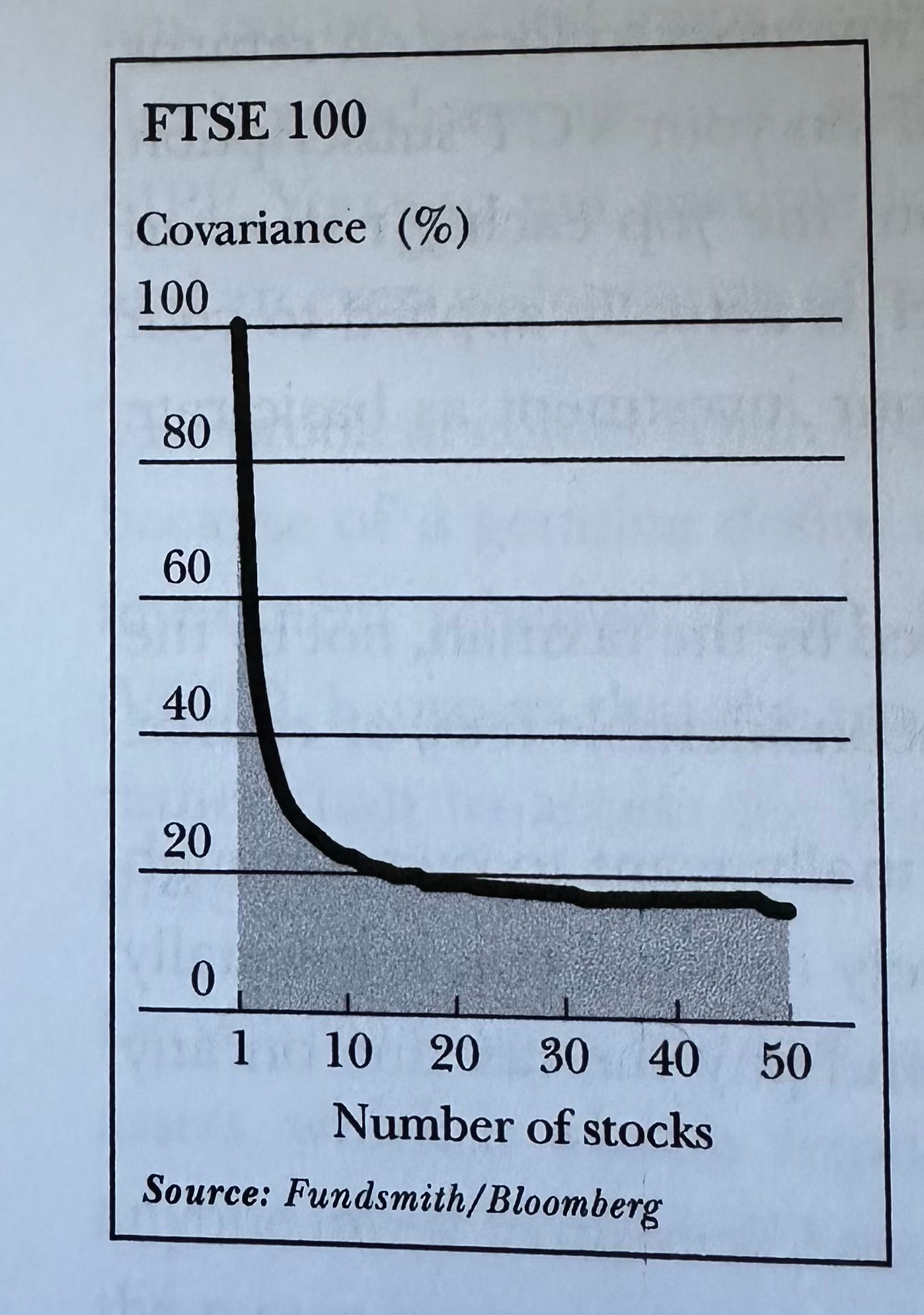

Data shows that adding more stocks to your portfolio significantly reduces risk up to a point. Going from 1 to 5 stocks cuts down a lot of risk, and moving from 5 to 10 helps too. However, after you hit 10 stocks, adding more doesn’t make much difference in risk reduction (see picture below). Plus, with the lesson of only investing in good companies in mind, there’s only so many quality companies out there. The more stocks you own, the more likely you are to compromise on quality and your understanding of each company.

Fund managers often own a ton of stocks to closely follow the index, making it harder to criticize their performance, even if they end up underperforming the index (despite charging high fees). For regular investors, it’s better to stick with a focused portfolio of high-quality stocks.

#11 Lessons Learned from his Best Investment (Domino’s Pizza)

One of Terry Smith’s best investments was in Domino’s Pizza. He wrote quite extensively about it over the years, so here are some of the key lessons from this investment:

Obvious Investments: The best investments aren’t always the obscure, hard-to-understand, or undiscovered ones. They’re often the most obvious.

Run Your Winners: People say, “No one got poorer by taking a profit,” but if you have a profitable investment, it might mean you own a share in a business worth holding onto.

High Return on Capital: This is the most important sign of a good business. Franchises excel here since most of the capital comes from franchisees, and the company earns royalties from their revenues.

Focus on the Product: Domino’s prioritized the quality of their food over accounting tricks when times got tough, showing the importance of focusing on the product.

Minimal Capital Requirements: Businesses that don’t need much capital to operate are better than those that do. Domino’s, primarily a delivery business, can operate from cheaper locations compared to restaurants that need high street spots.

High Leverage: In a business that can handle debt, high leverage can boost equity returns. As debt is paid down, value transfers to equity holders, reducing risk. However, this doesn’t mean leverage always enhances returns. Tom Gayner used this strategy when he bought AMF Bakery for Markel Ventures, which had a lot of debt but smooth operations.

Final Comments

I started with a quote and I’ll end with one I picked up in one of Terry Smith’s letters:

“Don’t just do something, sit there.”

This quote nails the importance of patience in investing, especially with high-quality companies. The secret to successful investing isn’t about chasing the latest trends or constantly tweaking your portfolio. It’s about being patient and letting your investments in solid, high-quality businesses grow over time. It’s not because of nothing that Francois Rochon says, "I consider patience to be the most important ingredient for success in the market." I’ll end it with that.

Thanks for reading the blog. I learned so much again and I’m really happy I finally finished this extensive blog on Fundsmith’s annual letters. Hopefully you learned something new as well, as we keep on compounding knowledge together. If you want to learn more about high-quality investing, follow me on X (@MindfulCompound) or leave a comment on the blog below. I’d love to hear from you!

Luuk

-

Disclaimer: This analysis is not intended as investment advice but as a personal opinion and can serve as a supplement to your own research. The information is explicitly not intended as advice to buy or sell certain securities or securities products, but to provide an overview of the underlying company/companies. You are solely responsible for the decisions you make regarding your investments.

Got a ton out of it! I agree with every word from my own personal learnings. Really appreciate the article!

great post, thanks :D