A Deep Dive into Dino Polska (DNP.WA)

Unpacking the Quality, Risks, and Future Potential of Poland's Retail Giant

My investment approach is all about finding high-quality companies that can steadily grow their value over the long haul. I look for businesses with a solid competitive edge, plenty of room to grow, a strong balance sheet, and great returns on the money they invest. Just as crucial is having a management team that's in it for the long run and has the right incentives. It might sound simple, but finding these high-quality gems is no easy task—it's both an art and a discipline. Let’s try to find out whether Dino Polska fits this description.

For transparency, I want to mention that Dino Polska is part of my portfolio (~10%), so I could be falling into some psychological traps, like confirmation bias or maybe even wishful thinking.

Just like I did with my Interactive Broker deep dive, I’m going to tackle Dino Polska by breaking it down into the following key questions to keep things clear and structured:

What does Dino Polska do?

Is it a high-quality business?

Is it run by a competent management team?

Is it available at a reasonable valuation?

What are the risks?

History of Poland

Before diving into the five questions, it's important to provide some context about Poland's history, more specifically their transition from communism to capitalism around 1990. Poland was under communist rule from 1945 to 1989 (44 years), following Soviet influence after World War II. However, before this, Poland had endured 123 years of partition, split between Austria, Prussia, and Russia, before regaining independence in 1918, only to lose it again at the start of World War II.

So, Poland spent over a century under foreign control, then had a brief period of independence, followed by decades of communism, before finally emerging as the free-market democracy we know today.

Since this awesome transition from communism towards capitalism, Poland did well by tripling their GDP per capita, PPP—a.k.a. their average income per person adjusted for the cost of living. Let’s go Poland!

The transition to a market economy attracted significant foreign investment, bringing in Western supermarket chains like Carrefour (from France), Tesco (from the UK), Lidl, and Aldi (both from Germany). However, not all grocery stores are the same and these large hypermarkets and supermarkets didn’t resonate well with Polish consumers. Hypermarkets, which combine supermarkets and department stores under one roof, and large supermarkets, focused on groceries and everyday items, struggled because Polish consumers often have less disposable income and live in smaller towns or rural areas.

With limited living space and storage, Poles tend to shop frequently, buying smaller quantities of fresh products rather than stocking up in bulk at hypermarkets. This consumer behavior is where Dino Polska excels. Let's dive into what makes Dino Polska so unique and why it stands out in this market.

What does Dino Polska do?

Dino operates what are known as “proximity supermarkets,” which are smaller stores located in residential areas where customers can easily walk or bike to shop. These stores are perfectly suited to Poland’s unique demographic and shopping habits, focusing on convenience and accessibility for people living in smaller towns and rural areas. The average basket size at Dino is about PLN 40.00 (~$10.00), reflecting the frequent, smaller purchases that fit well with Polish consumers' needs and lifestyles.

Dino is the fastest-growing chain in Poland, skyrocketing from just 111 stores in 2010 to around 2,500 by mid-2024.

There are a few standout features of Dino’s business model:

Strategic Focus on Small-Town Poland with Proximity Supermarkets

Owning Instead of Renting

Standardization and Internal Construction

Integrated Meat Processing

Low Catchment Area and Minimal Advertising

Rapid Expansion Strategy and Great Store Economics

Lowest Prices, Full Assortment and Highest Margins

Strategic Focus on Small-Town Poland with Proximity Supermarkets

Dino has taken a page out of Walmart’s playbook by focusing on small towns and rural areas in Poland with their proximity supermarkets, much like Walmart did in the U.S. This strategy works well in Poland, where about 40% of people live in rural areas. That’s quite a bit higher than in neighboring countries like Ukraine and Czech Republic, with The Netherlands being an extreme example (sorry, I just had to include it). Another thing to note is that this percentage has stayed pretty much the same for over 30 years, ever since Poland moved away from communism. By targeting these smaller communities, Dino effectively serves areas that bigger hypermarkets often overlook or find less profitable, since those big stores need a much larger customer base to make financial sense.

Owning Instead of Renting

One of the key strategies that sets Dino apart from its competitors is its decision to own nearly all of its store locations—around 95%, to be exact. In an industry where most companies prefer to lease their properties, Dino has chosen to invest in buying the land and constructing its stores from the ground up. This approach, while capital-intensive upfront, brings significant long-term advantages. By owning the land and buildings, Dino not only cuts down on long-term costs but also gains full control over its operations. For example, they can quickly make decisions like installing solar panels on more than 90% of their stores in a few years—a move that would be far more complicated if they were leasing.

Back in 2010, when founder Tomasz Biernacki sought external capital, he had a clear vision: transition from renting to owning. This capital allowed him to purchase land and construct each store, laying the foundation for Dino's rapid expansion. By 2013, Biernacki even launched Krot-Invest, a company dedicated solely to building Dino stores. This in-house construction team has significantly sped up the building process, eliminated the hassles of dealing with external contractors, and ensured that every new store adheres to Dino's standardized 400-square-meter blueprint.

Financially, this ownership model makes more sense for Dino in the long run. Studies show that by year seven, owning and constructing stores becomes cheaper than leasing. Given that Dino’s stores are built to last for decades and have never needed to close due to poor performance, this approach offers a sustainable financial edge over competitors who frequently close underperforming leased stores. It’s a clear sign that Dino is playing the long game. The fund Sohra Peak did a great job calculating the difference, I highly recommend checking out all of their research.

I must mention that buying property comes with its risks. What if a store doesn't perform well? Most retailers would simply end the lease and move on, offering them some flexibility. Dino doesn’t have that luxury, but here's the thing: Dino hasn’t closed a single store since 2007. Maybe not every store they've opened has been profitable, but the fact they’ve never even closed one and still earn high returns on capital is remarkable. So, while owning and building stores might seem riskier, for Dino, it’s actually a competitive advantage.

Standardization and Internal Construction

Dino’s decision to own its store locations isn’t just about cutting costs; it’s also the foundation for their success in standardization and internal construction. Every Dino store is built to the same specs—around 400 square meters with 5,000 different products and about 8-12 parking spots. This standardization is made possible because Dino owns the land and buildings, allowing them to maintain complete control over the design and layout of each store. Another sign that Dino—or really, their founder Biernacki—is super into standardization is that the Biernacki family actually owns the construction company that's completely dedicated to building Dino stores. That's pretty awesome.

Dino’s standardization across almost all of its stores is a big advantage. It makes opening new locations quicker and smoother while keeping the quality and customer experience consistent. Plus, because every store is basically the same, they can predict how well each new store will perform pretty accurately—something that’s tough for competitors who lease and operate with less standardized setups.

This uniformity also saves money in a bunch of ways. For one, it simplifies buying supplies and equipment because they can order the same stuff in bulk. Maintenance is easier too, since the stores are all designed the same way, so fixing things is straightforward. And when it comes to the supply chain, having a standardized layout means products can be delivered and stocked in a more efficient way, cutting down on time and costs. All of this adds up to a stronger competitive edge for Dino.

Integrated Meat Processing

Another thing that sets Dino apart is its focus on fresh, traditional meat counters. Since Poles have a deep-rooted preference for fresh pork and chicken, Dino ensures every store has a traditional meat counter as part of its offering. This strategy is backed by Dino’s full ownership of Agro-Rydzyna, a vertically integrated meat processing plant founded by the founder's family. This not only gives Dino full control over its fresh meat supply but also leads to higher efficiency and lower spoilage rates, which means better margins.

Unlike their competitors, who sell vacuum-sealed meat, Dino provides fresh cuts that appeal to the ~20% of Poles who eat meat daily and the more than 75% who consume it several times a week. Rumor has it that Poles are wary of packaged meat in large grocery chains, fearing lower quality, so Dino’s fresh offerings give them a competitive edge.

To keep up with demand and growth, Dino invested in the expansion of the Agro-Rydzyna meat processing plant and the construction of a smaller meat separation plant in a new meat processing plant, as is stated in their H1 2024 financial report, reinforcing its commitment to delivering fresh, high-quality meat.

Low Catchment Area and Minimal Advertising

Dino has a smart approach when it comes to store placement and advertising. Unlike its competitors, who rely heavily on advertising and need large catchment areas to hit their sales targets, Dino focuses on smaller catchment areas. Each Dino store only needs about 2,500–3,500 people living within a 2 km radius to be profitable, whereas discounters like Lidl need a much larger catchment area—around 20,000 residents within a 10 km radius—to turn a profit.

Because Dino’s stores are designed to be convenient for these local communities, they don’t require huge crowds to be profitable. This allows Dino to keep advertising costs incredibly low, spending only about 0.2% of sales on ads. Compare this to Lidl in Germany, which spends about 1.7% on advertising. Dino relies more on word-of-mouth and the convenience of its locations, which means customers naturally find their way to the stores.

This strategy not only keeps costs down but also ensures strong profitability while staying close to their customer base. It proves that bigger isn’t always better, especially when it comes to efficiently serving local communities. Even as discounters like Lidl rise, Dino’s low catchment area requirement and minimal reliance on advertising give it a unique and strong competitive edge.

Rapid Expansion Strategy and Great Store Economics

Considering all of this, it's clear that Dino has been on a remarkable growth path, going from 111 stores in 2010 to a bit more than 2,500 stores today, with an impressive CAGR of about 25%. The company isn’t slowing down either, aiming to increase its store count by about 20% each year. What’s interesting is that it typically takes about three years for a store to be fully mature. Considering that around 40% of Dino’s current stores (about 1,450 as of the end of 2020) are still under that three-year mark, there's a good chunk of profit still to be made. This means that in the next five years, Dino’s profits could potentially double just from the existing stores, even without opening any new ones. It also suggests that their current margins and returns are being held back by these new stores, and could be a lot higher once those stores start making money.

Sohra Peak did another awesome job at illustrating the store economics for Dino:

Dino’s stores start to become profitable after around three years. In the first couple of years, they’re still working to cover their initial costs, but by Year 3, they’ve hit their stride with operating margins climbing to about 8%.

From that point onward, things really pick up, with the Return on Invested Capital (ROIC) steadily increasing each year, reaching over 25% by Year 10. I find it really impressive how Dino manages to keep its operating expenses low as a percentage of sales. This steady rise in profitability means that even though it takes a few years for a new store to break even, once it does, it becomes a solid contributor to the company’s overall financial health.

Dino’s approach is all about playing the long game, with a focus on consistent growth and efficiency that pays off big time down the line.

Lowest Prices, Full Assortment and Highest Margins

Dino Polska manages to pull off something pretty impressive: they’re one of the cheapest grocery options in Poland, yet they offer a full assortment. Each Dino store is packed with around 5,000 items, covering all the basics—about 88% are essential groceries like bread, milk, eggs, and fresh fruits, while the remaining 12% includes non-food items like detergent, pet food, and cosmetics. What’s even more remarkable is that despite having a more comprehensive selection, Dino still maintains the highest margins in the business. This combination of low prices, a full assortment, and strong profitability makes Dino a standout player in the Polish grocery market. This is the last picture from Sohra Peak who, again, did a tremendous job visualizing Dino’s advantages:

You might be thinking, “How is it possible for Dino to be both close to the customer and the cheapest option around while enjoying the highest margins?” After all, basic economics tells us that convenience usually comes with a higher price tag. Think about stores like 7-11 or Żabka—because they’re so close to where you live or work, you often pay more for the convenience. So, how does Dino manage to stay close to their customers and still offer some of the lowest prices?

Here’s the secret (and I’ve told you already): Dino’s cost structure is different. First off, they own most of their store locations, so they’re not paying rent like many of their competitors. This alone cuts down their expenses significantly. Plus, Dino has its own meat processing plant, which gives them an edge in controlling costs and ensuring quality.

Even though Dino might sometimes be a bit more expensive for international products, they make sure to stay super competitive where it counts. They benchmark the prices of their best-selling 500 products against those of Biedronka, a leading discount chain, to ensure they’re offering the best possible prices. While some items might be slightly more expensive, Dino’s overall strategy keeps them in the game—and often, at the top—when it comes to offering low prices. The idea is to offer regional, quality brands (something Poles love) at prices that can compete with or even beat the big discounters.

So, Dino pulls off what seems impossible: being both conveniently close to the customer and consistently affordable. It’s all about a smart, efficient business model that defies the usual rules of economics.

Conclusion

To wrap things up, here’s what makes Dino Polska stand out from other grocery chains in Poland:

Focus on Small Towns

Owning Their Stores Instead of Renting

Standardized Store Design and In-House Construction

Emphasis on and Owner of Fresh Meat

Small Catchment Area and Minimal Advertising

Rapid Growth with Impressive Returns

Low Prices, Full Product Range, and High Margins

In short, Dino stands out by staying close to customers, offering a wide selection, and being one of the cheapest options around—all while pulling in the highest margins in the industry.

Is it a high-quality business?

I’ve already covered a lot of what makes Dino stand out in the first question of this blog, but now I'll shortly revisit those key points to outline their strange competitive advantage, and also dive into some numbers to show why Dino is more than just another grocery chain.

Dino Polska's Competitive Advantage: A Lollapalooza Moat

Dino Polska has crafted a unique competitive advantage by doing several small but impactful things differently. These differences combine to form what’s known as a “Lollapalooza moat”, a concept of Charlie Munger. It refers to the idea that when multiple smaller factors work together, they create a powerful advantage. I’ve already covered these points earlier in the blog, but I want to quickly outline them again to show how they really strengthen Dino’s moat.

1. Owning Instead of Renting: Unlike most retailers that lease their store locations, Dino owns nearly all their land and stores, which gives them total control over costs and operations. They can make long-term moves, like installing solar panels on most stores, without dealing with the hassle of lease contracts. This keeps costs down and makes it harder for competitors to keep up.

2. Cost Efficiency through Standardization: Dino has nailed down a standardized store design, so every location looks and runs the same. This keeps costs low and makes it easier to open new stores quickly. Competitors who don’t have this consistency end up with higher costs and less predictable results, giving Dino the upper hand.

3. Vertical Integration in Meat Processing: By owning their meat processing plant, Dino controls a key part of their supply chain, which helps them keep quality high and costs low. This gives them better margins on fresh meat, which is a big deal for Polish shoppers, and makes it tough for competitors to offer the same quality at similar prices.

4. Low Catchment Area Requirement: Dino can succeed in smaller towns where bigger competitors can’t, thanks to needing fewer customers to turn a profit. This lets Dino dominate in markets that aren’t worth the trouble for larger chains, strengthening their presence in those areas.

5. Minimal Advertising Costs: Dino’s smart locations and strong word-of-mouth mean they don’t have to spend much on advertising. By keeping ad costs super low, they boost profitability, which gives them a cost advantage over competitors who spend way more on marketing.

6. Strong Value Proposition and Competitive Pricing: Dino really stands out by offering a full range of products at some of the lowest prices around, all while being super convenient for customers. They make sure their prices on key items are as low as the competition, but what makes them different is that they do this without cutting into their profits. Thanks to their efficient setup, Dino can keep prices low, offer a wide selection, and still be right where customers need them. This makes them a strong player in the Polish grocery scene.

These small, smart decisions add up to something much bigger, giving Dino a solid moat that keeps them ahead of the competition for some time to come.

Competition and Growth Potential

Essentially, Dino is growing in two main ways:

Opening New Stores: Dino has been on a roll, boosting its store count by around 20% each year since 2014, growing from 400 to 2,500 locations. This bold approach has really ramped up Dino's market presence across Poland. While the pace of opening new stores has slowed recently for various reasons, management mentioned in their Q2 2024 earnings call that things will speed up again next year. The compounding engine is still going strong!

Increasing Sales in Existing Stores: Besides just opening more stores, Dino is also focused on boosting sales at its existing locations. This is what's known as “like-for-like or LFL” sales growth, and it’s a key indicator of how much customers value Dino. The impressive part is that Dino’s like-for-like sales have been growing faster than food inflation in Poland over the past few years. This means that more customers are choosing Dino for their regular shopping needs, and they’re spending more when they do.

You can see that the like-for-like (LFL) sales are on a downward trend, and in Q2, Dino's LFL sales even fell below food inflation —definitely not a good sign! But if we compare this with their main competitor, Biedronka, they're doing even worse, with a drop of 4.6%.

I don't usually focus on short-term info in these deep dives—I prefer to keep things more timeless and structured. But it’s worth quickly touching on a few factors impacting Dino's like-for-like (LFL) sales to understand why they’re taking a hit right now:

Drop in Food Inflation: The bigger issue is the drop in food inflation, down to 2% from 21% a year ago. Since 88% of Dino's revenue comes from food and drinks, this decline hits hard.

Price War in Poland: The main factor is the ongoing price war in Poland. Dino, Biedronka, and Lidl are all cutting prices to stay competitive, which is squeezing everyone’s sales and profit margins. At the quantitative section, I’ll dive into why I believe Dino has a good chance of coming out stronger, potentially gaining market share.

Future Growth

What about the future? Can Dino keep up the growth and performance? Dino's strong competitive advantages— focusing on small towns, running smaller more efficient stores, owning their land, delivering fresh meat, and skipping advertising—make them stand out and tough to beat. I’m confident Dino will keep growing quickly in the coming years, just as management has hinted in their Q2 2024 call.

How many Dino stores can fit in Poland?

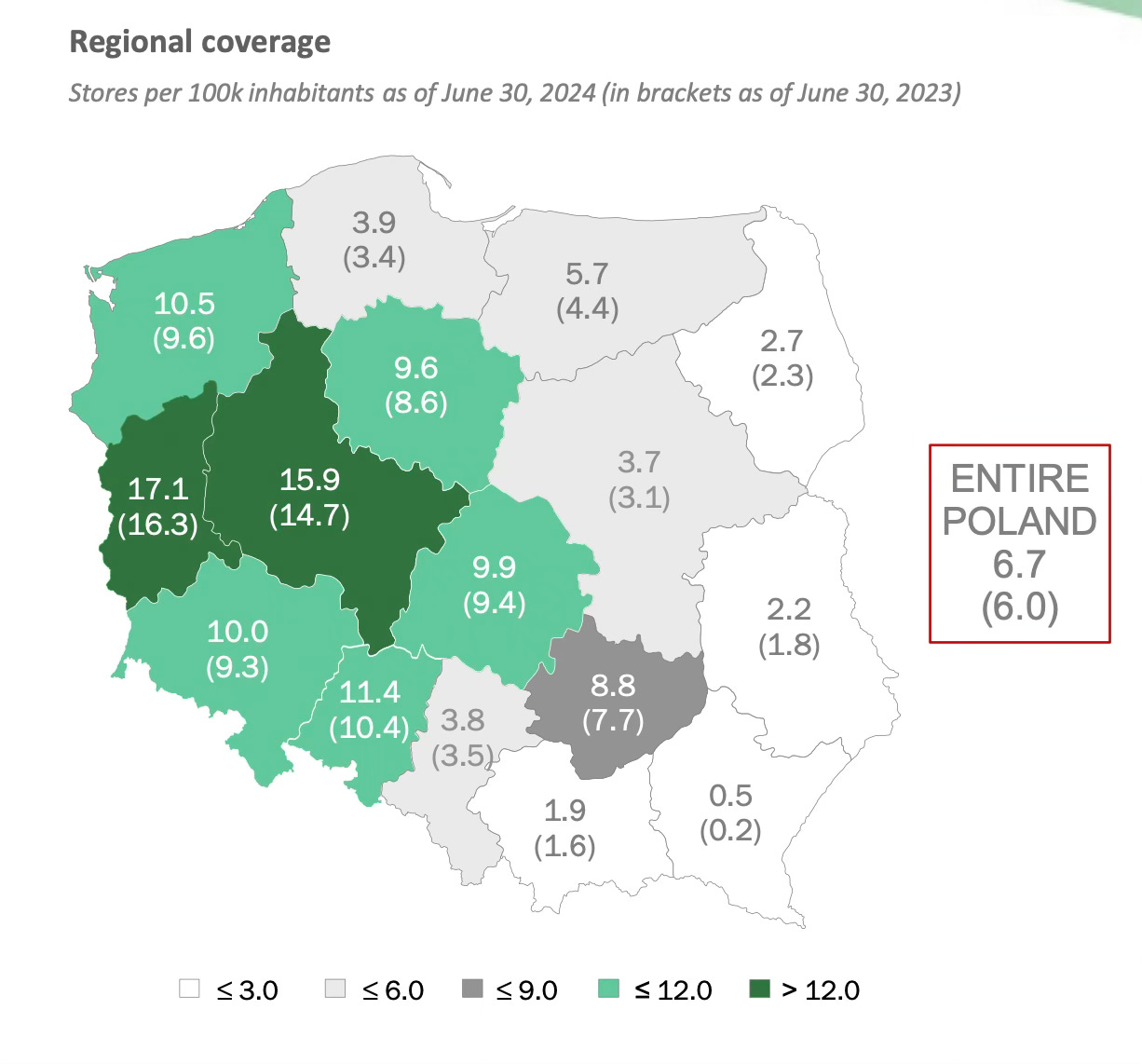

As you can see in the picture above, Dino started in the two dark green western provinces, which now have around 17.1 and 15.9 stores per 100,000 people. There’s still plenty of room to expand eastward, even though that part of the country is still developing. I don’t see any reason why the rural areas in Eastern Poland would be much different from those in the West. However, the profitability of Dino's new stores in the East is crucial for predicting future growth. We don’t know for sure if these new stores will be profitable, so it’s important to trust management's decisions on where to invest.

I trust management, so if we assume the whole of Poland could reach around 15 stores per 100,000 people, like the western provinces, Dino could potentially grow to 5,700 stores nationwide. This would more than double their current count of around 2,500 stores.

I believe 15 stores per 100,000 people is a reasonable estimate. It's a bit lower than what we see in these two Western provinces, but Dino stores do well in communities with just 2,500 - 3,500 people. Considering that rural areas across Poland are pretty similar, and Dino has been opening stores nationwide without closing any since 2007, this estimate seems fair to me.

Quantitative evidence

Return on Capital & Reinvestment

The success of my investment in Dino depends on whether management can continue opening new stores profitably—essentially, whether they can invest capital with high returns. But it’s not solely about high returns; Dino also needs strong reinvestment opportunities to truly become a compounding machine. Let’s break it down:

Dino’s capital expenditures (CAPEX) cover key areas like opening new stores and expanding logistics with new distribution centers. In H1 2024, Dino also spend cash upgrading the Agro-Rydzyna meat processing plant, and building a smaller meat separation facility.

The company is reinvesting heavily into organic growth, primarily by opening new stores. It’s important to know that CAPEX can be split into two parts:

Maintenance CAPEX

Growth CAPEX

Ideally, you want to spend as little as possible on just maintaining what you have (maintenance CAPEX) and put more money into expanding and growing (growth CAPEX), as long as those growth investments keep giving you good returns.

How did Dino fare in 2023?

Dino spent about 1.2 billion Polish zloty on CAPEX.

About 350 million zloty was spent on depreciation and amortization, which we can generally assume is close to their maintenance CAPEX. But for Dino, since a lot of their stores are pretty new, their maintenance CAPEX is actually lower than D&A because new assets typically require less maintenance.

This leaves about 850 million zloty for growth CAPEX (1.2 billion minus 350 million).

Their operating cash flow was around 1.8 billion zloty, so Dino didn’t reinvest 100% of their cash flow back into the business, unlike in previous years. This shift was due to a tougher macroeconomic environment, leading management to take a more cautious approach by paying off some debt. I expect them to get back to reinvesting fully in the years ahead.

As I mentioned earlier, heavy spending on growth CAPEX is fantastic—provided the reinvestments are generating high returns. Dino is a perfect example of this, almost always reinvesting 100% of its operating cash flow back into the business - while maintaining a high Return on Invested Capital (ROIC) of averaging higher than 15% since 2014 and even 20% as of 2023. As you could see in one of the Sohra Peak images, a store generally returns ~20% in Year 4 and that number only gets higher as time progresses. That's how you build a compounding machine!

Balance Sheet

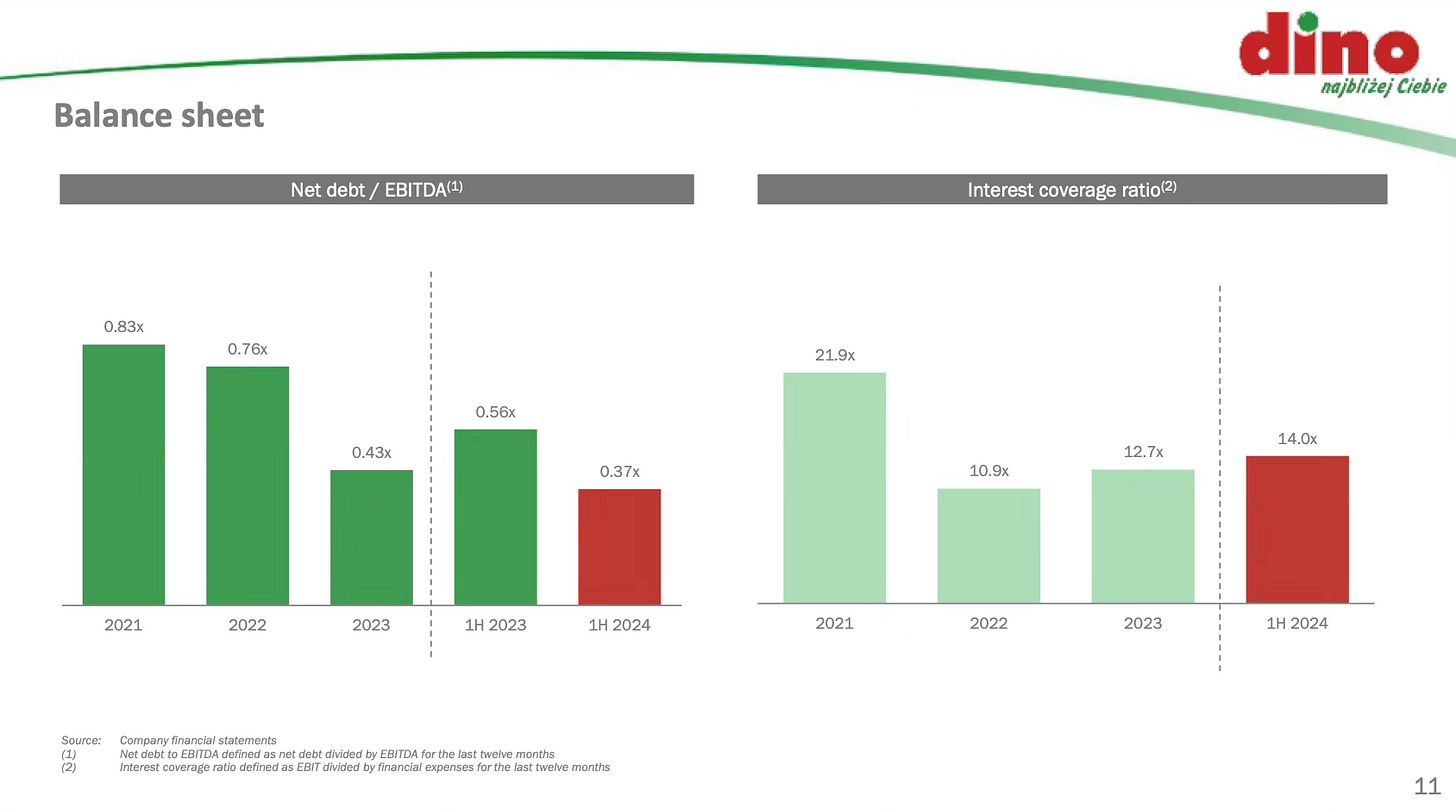

Dino's financial health looks solid with a net debt to EBITDA ratio of just 0.37. This means that Dino could pay off all its debt in less than half a year using its earnings. Of course, you cannot pay off debt with EBITDA, but it’s an indication for cash flows.

Dino’s interest coverage is ~14x which means that Dino's profits (EBIT) are nearly 14 times higher than what they need to pay in interest, showing they’re in a solid position to easily handle their debt payments.

Compared to Dino Polska, their main competitor, Biedronka (owned by Jeronimo Martins), is in a much weaker financial position. As of the first half of 2024, Biedronka's Net Debt/EBITDA ratio is about 3, with net debt sitting at 3.2 billion and EBITDA at 1.04 billion. To make things worse, Jeronimo Martins' interest coverage ratio has dropped from 6 times in 2022 to around 4 times now. On top of that, they’ve paid out around 400 million in dividends, unlike Dino, which hasn't paid any. All of this paints the picture of a financially unstable company.

So why bring up Biedronka’s finances when we’re talking about Dino Polska? Well, competition in the Polish grocery market has been heating up (i.e. a price war). Biedronka holds more than 25% of the market, while Dino is under 10%. But with Dino’s stronger balance sheet and without their obligation to pay out dividends, I believe they’re in a good position to start taking market share from Biedronka when the price war persists.

Margins

Dino has solid margins, with a gross profit margin of 23%, an EBITDA margin around 8%, and a net profit margin between 5-6%. Their net profit margins have steadily increased from around 3% in 2014 to some of the highest in the global supermarket industry. This reflects their strong competitive advantages turning into solid profits. However, in H1 2024, Dino’s EBITDA margin dipped from 8.5% (H1 2023) to 7.3%, mainly due to the ongoing price war in Poland. I expect this price war to continue, so margins might shrink further in the near term. But as a long-term investor, I’m not worried. Why?

Let’s compare Dino to their closest competitor, Biedronka, whose margins are lower: around 20% gross profit margin, 5-6% EBITDA margin, and just a 2% net profit margin. Biedronka’s parent company, Jeronimo Martins, operates in Colombia, Portugal, and Poland, but these numbers give us a good idea of what Biedronka is up against in Poland.

In a price war, having worse margins makes it harder to compete because there’s less room to cut prices without hurting profitability. Dino’s better margins mean they can lower prices and still come out ahead, while Biedronka would feel the financial strain much more. When you factor in Jeronimo Martins' overall financial health, which I mentioned earlier, it’s clear that Dino is in a stronger position.

Investing in higher-quality companies like Dino means they can keep reinvesting during tough times, gaining market share from weaker competitors. I believe Dino will come out of this price war with a larger market share and, once things settle down, will hopefully return to their higher margins thanks to their better capital structure and increased market presence. As a long-term investor, I’m willing to wait for that.

Negative Working Capital

Finally, I’d like to shortly discuss the clever and efficient way of Dino’s growth strategy, which is partly fueled by what's called "negative working capital." Here’s how it works: Dino pays its suppliers after about 50 days, but it gets paid by its customers much faster than that. This timing difference means that as Dino grows, it actually generates more cash instead of needing more cash to grow. So, even though the company spends a lot on new stores and improvements (Capex), this negative working capital helps keep the cash flow positive.

Is it run by a competent management team?

Let’s talk about Dino’s management, which is quite unique. The company doesn’t have a traditional CEO. Instead, Tomasz Biernacki, the founder, serves as the Chairman of the Supervisory Board and is allegedly still heavily involved in the company’s strategy. What’s interesting is that during Dino’s IPO in 2017, Biernacki wasn’t even present. He’s a very private person—you won’t find much about him online. In fact, if it were up to him, Dino probably wouldn’t have gone public, but the private equity investors wanted to cash out, so they had to.

Despite not being the CEO, Biernacki is still very much in control. He’s more focused on running and expanding the company rather than getting caught up in the spotlight. He’s never sold any of his shares, which says a lot about his long-term commitment. Even though he’s the second-richest person in Poland, he prefers to stay under the radar and can shop anonymously in his own stores, which is pretty awesome.

Overall, Dino’s management isn’t about flash or glamour—they’re all about making smart, long-term decisions that benefit the company in the long run. Everything is done with a purpose (like opting for the cheapest trash cans), and it’s all in line with their goal of continued growth and success. For example, they set up their headquarters in Krotoszyn, a smaller, less flashy town compared to the capital, Warsaw. This choice aligns with the founder’s vision to target customers in rural areas and keep costs low. I love it.

Dino Polska’s management team is a big reason why the company has been so successful. Here are four standout qualities that make them special:

Founder-Led with Strong Insider Ownership: Dino is still led by its founder, Tomasz Biernacki, who owns a solid 51% of the company. This ownership level has stayed the same since 2010, showing his long-term commitment. At around 50 years old, Biernacki has plenty of time to keep growing Dino's value, and his active involvement as Chairman means he’s deeply invested in the company's future.

Smart Capital Allocation: The management team at Dino is all about making smart, long-term decisions. They’ve chosen to reinvest nearly all of the company’s cash flow into expanding the business, rather than paying out dividends. It’s a great decision to not pay out any dividend when you can earn great returns on your capital. In Dino’s case, they reinvest all of its earnings back into the business generating a more than 20% return on capital.

Long-Term Focus: Dino’s management isn’t just looking for quick wins—they’re in it for the long haul. They’ve made strategic decisions like owning stores, even though it takes about nine years to break even compared to the cost of leasing, and price-matching discounters even during inflationary times. Another long-term move was installing solar panels on now more than 90% of Dino stores shortly after the energy crisis hit. The management acted quickly to protect the company from skyrocketing energy prices, demonstrating their focus on long-term sustainability and cost efficiency. These choices show they’re more focused on long-term profitability than short-term gains, which is a big plus for the company’s future success.

Experienced and Stable Leadership: Besides Biernacki, the three other key members of Dino’s management team have been with the company for over 20 years now. Izabela Biadałan and Michał Krauze, who joined the board in 2021, have been with Dino since 2002. Piotr Ścigała, who joined the board in 2022, has also been with the company for a long time, since 2003. This kind of long-term leadership gives Dino a strong foundation, ensuring continuity and consistency as they grow.

Overall, Dino’s management team is not just experienced but also deeply aligned with the company’s long-term success, making them a major asset to the business.

Is it available at a reasonable valuation?

I’ve already covered a lot, so I’ll try to keep the valuation part straight to the point. In the first half of 2024, Dino earned 6.6 zloty per share, meaning the stock, which today trades at around 330 Polish zloty, is currently trading at around 23 times earnings.

When it comes to Dino, I’m confident that their growth story has plenty of room to run, especially with their competitive advantages still going strong. I’ve noticed that their biggest competitor, Biedronka, seems to be struggling even more and might eventually have to downsize. As I mentioned earlier, this could open up long-term opportunities for Dino.

Now, let me walk you through the scenario analysis:

Revenue Growth: The revenue growth comes from two main sources: Like-for-Like (LFL) sales growth and the opening of new stores. I’m anticipating LFL sales to grow by 8-12%, which lines up with the average of around 13% over the past decade (partly boosted by higher food inflation in 2022, as you can see below). The other half of the growth will come from new stores, with management planning to open about 300 new stores each year for the next 4 to 5 years. So, when you factor in new stores, higher volume, and price increases, you’re looking at 15-20% overall growth. However, opening another 300 stores on top of the current ones might slow the growth rate a bit, which is why I estimate revenue to grow 16% annually for the next five years.

Net Profit Margin: Over the past three years, the net margin has hovered around 6%, slightly higher in 2020 and a bit lower at the moment. With 1,200 relatively new stores that could become more profitable as they mature, and with Dino's growing bargaining power, higher margins are likely. However, I’ll assume the margin will stay around 6%.

Exit Multiple: A multiple of 20 seems fair for a slower-growing company like Dino after five years. Plus, it makes sense when you consider that their competitor, Jeronimo Martins—who isn’t as high-quality—trades at around 16 times earnings.

This scenario points to an IRR of ~16%. But keep in mind, if the multiple, revenue growth or margins drop, so will the returns. There are, of course, tons of possible outcomes depending on how these key figures play out. This is just my model to track Dino’s performance based on the numbers I’ve currently used.

If margins creep up to 7%, which isn’t out of the question for the reasons I mentioned earlier, your IRR could be around 20%. But be cautious—high margins are rare in the supermarket industry, where most players operate with slim net profit margins. Dino might be an exception based on everything I’ve discussed, but it’s still something to watch.

To sum it up, my estimates suggest Dino could deliver a potential CAGR of 16-20%. Just a quick reminder, this isn’t investment advice. If for example Dino can’t successfully expand in Poland, your returns could be much lower, possibly even negative. That’s why it’s so important to keep the risks in mind.

What are the risks?

As with every investment, there are multiple risks involved! These are the ones I found for Dino Polska, but remember there must be tons more:

Geopolitical Risk: Dino operates in Poland, right next to Ukraine, so any even bigger escalations in that region could impact business in Poland. This proximity might also make some American investors wary due to the associated reputational risks. Maybe you know the quote: “Nobody ever got fired for buying IBM”.

Founder Dependency: Tomasz Biernacki, Dino’s founder and current chairman, has been crucial to its success. Even though he’s only about 50 years old, the company’s heavy reliance on his leadership could be a potential risk.

Increased Competition: As Poland’s economy grows, there’s a risk of increased competition, especially in small-town areas where Dino currently dominates. Competitors like Biedronka might push into these markets, challenging Dino’s edge in proximity and fresh meat offerings.

Food Scandal: Talking about their fresh meat offerings, since Dino is vertically integrated and owns its meat processing plants, there’s always a reputational risk if a food scandal were to occur, which could hit the brand hard.

Online Grocery Shopping: While online grocery shopping is still a small part of the market (less than 1%), it’s growing. Dino’s strength as a local, convenient store might protect it more than hypermarkets, but it’s still a trend to watch.

Execution Risk: Dino’s ambitious goal of opening one to two new stores every business day carries execution risk. However, their management team’s solid track record suggests they’re up to the task.

I'm a huge fan of Morgan Housel, and he has this spot-on quote about risk: "The biggest risk is always what no one sees coming. It’s what the crowd dismisses as a potential risk because if everyone saw it coming, it would have been handled." That’s exactly what could happen with Dino Polska, or all other investments of course. I don’t put all my eggs in one basket and try to diversify according to my risk tolerance.

Thanks so much for sticking around till the end! This deep dive took a lot of work, but I had a blast and learned so much about Dino Polska. I hope you did too. If you want to chat, feel free to message me on Substack or on X (@MindfulCompound). I'd love to hear your thoughts. Thanks again, and see you in the next one!

Luuk

-

Disclaimer: This analysis is not intended as investment advice but as a personal opinion and can serve as a supplement to your own research. The information is explicitly not intended as advice to buy or sell certain securities or securities products, but to provide an overview of the underlying company/companies. You are solely responsible for the decisions you make regarding your investments.

Great read Altea!

one of my highest EU convictions